Harry Everett Townsend ( 1879 – 1941)

This article profiles a struggling time, 1933 – 34, in the life of artist Harry Everett Townsend. His story is one part of a much larger New Deal narrative that will circle back to the National Archives (NA) and the inadvertent retention and rediscovery of “orphaned” * New Deal “business files”. These financial files were generated during the short lifespan of the first federal art program, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), they dovetail and compliment other known New Deal collections at the NA and add factoids previously unknown.

There are a wealth of books and articles written about Harry Everett Townsend, but none address this soul crushing and devastating Great Depression period in his life. Suffice to say, Townsend, although well known and established, was an artist desperate for work. He would come to find relief and purpose with the various federal art programs; employment which saved him financially and emotionally.

It wasn’t until he was sent to depict the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) that he was once again in his element. As a WWI veteran combat artist he saw his employment with the PWAP as an opportunity to repay a debt to America, fulfilling a commitment he felt was long overdue.

_______________________________

Harry Everett Townsend

1930’s HARD TIMES

” I am in trouble and truly sick at heart . . . one is ashamed to face the world.”

Harry Everett Townsend – 1930’s Hard Times

The crushing talons and depth of the Great Depression did not bypass the renowned WWI combat artist Capt. Harry Everett Townsend . . . by 1934, his financial circumstances were beyond dire.

The early 1930’s demographics place Harry with wife Cory, also an artist, and their daughter (Bettina) Barbara, a student, living and working in Norwalk, Ct. The local directory lists the Harry Townsend Studio at 10 Stevens Street, a property said to include a barn; ideally suited as a dedicated space to create. During the cruelest years of the Great Depression Harry was competing for the little available work for any artist in the NYC metropolitan area.

Sadly, by 1933, after an attempt to stave off a looming foreclosure Harry borrowed from friends, then took another loan, this time with the Home Owners Loan Corporation, a commitment which sent him deeper into debt and despair. He was humiliated and consumed with worry.

Then came a life-line, some steady income, that kept him afloat. It was the first ever federally supported art program, the Public Works of Art Program (PWAP).

Harry Townsend and the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP)

The first government sponsored art program, the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), began December 8, 1933 and lasted until the spring of the following year. Employing 3,749 artists along with the hundreds of administrative office staff. The program provided much needed and meaningful employment during the harsh winter of 1934. Selected artists would work independently with the understanding their contributions would become a new type of art, an American art. The PWAP working theme was suitably “the American Scene”.

Harry Townsend was informed of the program and was grateful when invited to join the PWAP district closest to him. The lower 48 states were divided into sixteen geographic regions. Region 2 included NYC, and the commuting zones of New Jersey and Connecticut. The Reg. 2 Director was Mrs. Julianna Force, also the formidable Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Each region had a strict quota which limited the number of artists employed.

In Reg. 2, a turnstile solution was instituted for “Separations” and “Replacements” of artists. . . It was an uncomfortable situation when dismissal notices were sent to already distressed artists, but the replacement artist was unemployed and equally distressed. There was a long wait list in Reg. 2, tensions would become high; thousands of artists were clamoring for this guaranteed work being sponsored by the government.

Townsend, like all artists vying for the few positions available, needed to make an application and submit samples of his work. His dilemma was not knowing the type of work to submit. He provided “a number of photos and two lithographs (among other things) of military subjects. . . if I’ve made any sort of a mistake in submitting these – I should like to submit a type of easel picture I am known by “.

Townsend felt obligated and seems to have viewed his contributions to this new federal art project through the prism of the months he’d spent in 1918, as a WWI American Expeditionary Force (AEF) combat artist. His AEF endeavors were cut short because the conflict ended with a rush. Townsend held a firm belief that, with additional time he could have done more, a sense of purpose he penned in his war diary, and again in his PWAP letters.

Townsend felt a time would come to create great war pictures that would merit attention, thereby justifying his selection as an official AEF artist. He felt a patriotic responsibility that may not have been initially understood by the PWAP Reg. 2 committee. After his dismissal he sent an impassioned letter addressed to Julianna Force, explaining his dire situation, reasoning and commitment. This plea for reinstatement was dispatched to the decision makers in DC. who came to understand and respect the debt Townsend felt to the cause.

The CCC and the PWAP

There were mandated goals the PWAP were required to meet; one focused on the government works project. In late January of 1934, priority would be given to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a popular New Deal program and a favorite of President Roosevelts.

Because of timing and harsh winter conditions, less than three dozen PWAP artists were sent into CCC camps nationally, they were called “roving artists”. Some would spend a day or weeks at CCC camps, they would bunk and dine with the technical staff. Their experiences and art would spawn another New Deal program when the PWAP ended, in June 1934, the CCC Art Program.

Julianna Force’s PWAP administration was well organized and geographically well positioned; Reg. 2 would assign eight of their PWAP roving artists to CCC camps. Ironically, the same number of WWI AEF combat artists sent to France, except this time, Townsend’s assignment was to artistically depict a different type of army, the CCC Tree Army.

————————————

Harry Everett Townsend PWAP ARTIST #400

Townsend’s first PWAP employment began shortly after the 1934 new year. He reported to the PWAP NYC headquarters on 8 W Eighth Street, known as the Whitney Studio. There he met with Harry Knight, Jr., Asst. Chief Clerk , and discussed the work he would produce for the PWAP – Harry had hoped for a mural project, which was nonexistent. After some discussion he left with the understanding he would instead focus on easel paintings and art that depicted “war landscapes”. Knight gave what Townsend believed was approval.

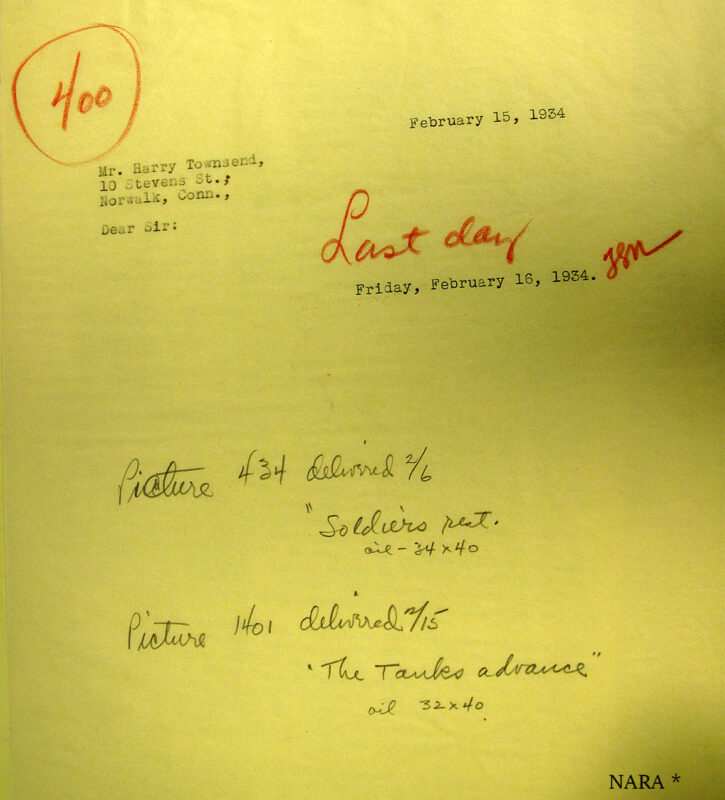

Signing on January 10, 1934, as PWAP artist #400, he was judged to be a Grade A artist and received his first full weeks salary, of $34, the following payday. With the guarantee of a weekly check he felt overwhelming relief; he was now able to meet his obligations. Over the next month, working from his Norwalk studio, Townsend produced and delivered two oil paintings; “Soldiers Rest” (Flirey)( France)) and “The Tanks Advance”.

Initially the PWAP funding was to cease in mid-February, widespread belief was that Congress would approve an extension beyond the Feb. 15th deadline, which they did.

PWAP Reg. 2, in anticipation of this deadline, posted letters to all artists, instructing them to deliver all finished and unfinished art to the Whitney Studio PWAP Eighth Street location by Feb. 15th; a number of these notices contained the “bad news”; they were being dismissed from the project.

Aware of the Congressional deadline Townsend made his delivery on deadline, he “asked again, anxiously, as to whether or not in case of the work going on, I would carry on“. Townsend was assured he would be allowed to carry on.

The next day, Feb. 16, 1934, Harry was stunned to receive his PWAP notice of dismissal, he was blindsided.

In panic and fear, he penned, actually he typed a two-page, single spaced letter to Mrs. Julianna Force, Director of PWAP Reg. 2, pleading his case and begging for reinstatement. He confessed that the past three years have been a “veritable hell“, he had crushing debt, and reminded her of his AEF WWI veterans status and his belief that military art was still relevant.

It is clear from Townsends letters, and a must read for those studying the New Deal artists, the PWAP program had been “an answer to a prayer”. It was the sudden dismissal that left him with “the old problem and not being able to meet it.” His fear is palpable, when he asks “why?”, and then he questions if he had been misunderstood?

Harry E. TOWNSEND CCC Assignments

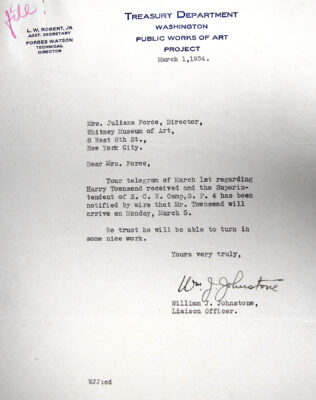

Reg. 2 Director, Mrs. Julianna Force acted immediately after receiving this impassioned plea. Telegrams and letters were sent to the powers that be at PWAP central headquarters in Washington, D.C. Townsend’s 2nd PWAP enrollment was OK’d. This time he would be given an assignment as a “roving” artist, visiting Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps, provided Reg 2 did not exceed their artists quota.

On Saturday, March 5, 1934, Harry was once again entered in the payroll ledger as a new PWAP artist # 675, this time with a weekly salary of $38.25. All train or bus travel, along with expenses, were covered. He also received a daily stipend for subsistence at the camps.

Leaving Norwalk that same day on the 9:03 am train, then switching at NY Penn Station, Harry arrived around noon at the Cold Springs, NY train station. Using a pay phone, costing 50 cents, he called the “Iron Mine” CCC office for a ride to the camp to begin his artistic depiction of the CCC enrollees and the work project for CCC Co. #209.

For the next five days Townsend ate, slept and immersed himself sketching the life and work at the Clarence Farnestock Memorial Park CCC camp, Co. 209, SP-4. He acclimated easily to the quasi-military lifestyle of the CCC and returned the following Wednesday, by train, to Norwalk to complete his work.

Townsend set out again, on April 5th, for another CCC camp in Ithaca, NY, SP-16, Co. 1205. This camp layout was completely different, “the boys barracks is a large factory building on the edge of Ithaca, everything contained in one building – with Bowling Alley and a large kitchen“. Their projects were landscaping in the surrounding parks and constructing a spillway, in Buttermilk Falls State Park. Harry felt the parks were beautiful, despite the rain, and wanted to spend a few extra days, or even return in the spring, he was filled with ideas as he was working on a “few large pictures” and “character studies” . From these two CCC assignments Harry delivered a minimum of 41 pieces (water colors, charcoal, crayon, drawings) which were forwarded to DC headquarters for allocation.

Harry Townsend remained with the PWAP program as a “roving artist” until all remaining artists in Reg. 2 were furloughed on April 29, 1934, as the PWAP ended. Within two months, an unusual government art program had spawned from the PWAP, a new program was launched which sent artists into CCC camps. A project personally approved by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR), the CCC Art Program.

Harry remained in Norwalk for the rest of his life and found meaningful artistic employment with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). On November 20, 1935, Townsend was reassigned to a new and larger New Deal program, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Federal Art Project (FAP)

His work as a WPA FAP artist was extremely productive. A listing of his 87 WPA paintings and murals are included with his biography on the Connecticut State Library website.

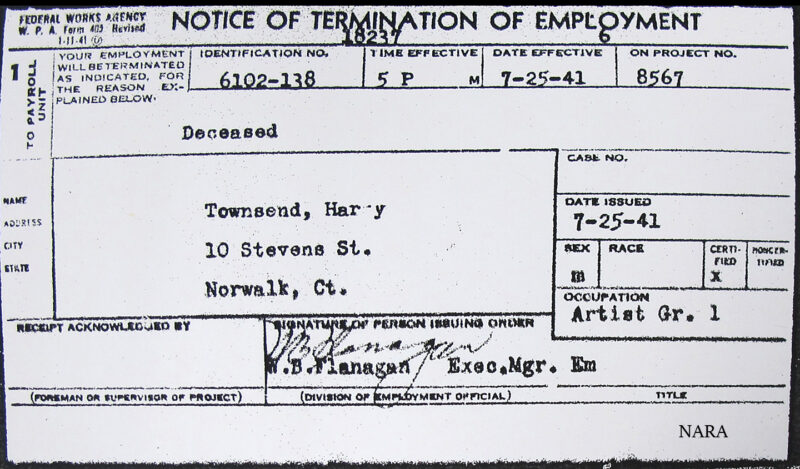

Harry Everett Townsend remained a New Deal artist until the end of the business day, 5 pm, Friday, July 25, 1941. He was 62 years of age when he succumbed to a coronary event later that evening.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS and NOTES –

This narrative is a work-in-progress. This information will be addressed.

- * “orphaned” files – Payrolls and Daily Employment Records, Official Personnel Folders-Public Works of Art Project, Works Progress Administration, Record Group 146: Records of the U.S. Civil Service Commission; National Archives, St. Louis, MO NAID 3768785

———————————————